Cleveland Indians’ “Chief Wahoo” baseball pennants from Lafayette, Indiana (1950s–present)

Andrew Seng

"Chief Wahoo, adopted as the mascot for the Cleveland Indians in 1947, and other Native American–inspired iconography have been used and normalized by the sports world for well over a century."

Andrew Seng is a Brooklyn-based photographer whose work explores themes of race and identity in American culture. His ongoing photo series Made in the USA: A Portrait of America’s Racist Ideology Through Items and Artifacts confronts these concepts head-on by exploring how racist ideologies can permeate popular culture and how these ideas can manifest in the items we buy.

Seng’s photographs document consumer items that include offensive imagery and stereotypes — some of which continue to be sold in stores today. It’s Seng’s hope that his photographs will start a conversation and help to educate people on how the legacy of racism has shaped America as we know it.

Here, Seng discusses the concepts behind Made in the USA and shares a selection of photographs from the series.

What do you want people to take away from this body of work?

Andrew Seng: Made in the USA is a study on objects from the past and present that embody and perpetuate casual racism. The ongoing series takes a look at how racist ideas are commodified, disseminated, and how they are intentionally weaponized to achieve particular goals and influence ways of thinking. I think that it’s critical to understand that we live in a country built on a foundation of white supremacy that allows for these racist items and racist ideas to exist.

I hope this work can be a point of education, but also a body of work that encourages people to question their implicit biases or their preconceived notions that have been systematically, systemically, and purposefully entrenched in American values and views.

Aunt Jemima salt-and-pepper shakers from Fort Madison, Iowa (year unknown)

Andrew Seng

"The mammy caricature was developed during slavery and widely used in minstrel shows, consumer products, and in early American films such as The Birth of a Nation and Gone With the Wind."

“Build the Wall” block set from Dallas, Georgia (2018)

Andrew Seng

"Studies by the American Immigration Council show that immigrants commit fewer crimes than native-born people of comparable age in the US."

As a person of color in America, I grew up seeing a lot of racist depictions and racist tropes that made me feel awful. When you’re a kid, you may not yet have the words to describe what you’ve seen or heard, but you know that it’s not good. I think that seeing the same type of imagery hundreds of times over can have an effect on a person’s psyche. Representation is so important because it not only teaches other people how to see us but how we see ourselves.

What were some of the challenges you faced in completing this work?

AS: I was concerned and continue to be concerned that by putting out this work that I’m just perpetuating the hurtful narratives and the hurtful intended purpose of the items that I am discussing. I’m constantly interrogating who the intended audience is for this project, and I grapple with the question of whether I should be the one telling these histories.

So my challenges stem from a moral and ethical standpoint. I hope that people will see the importance in having these discussions, just as David Pilgrim, professor and founder of the Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia at Ferris State University, sees the importance of keeping these hateful objects in a permanent place of learning and education.

Vintage chalkware “Coolie” head from Kalispell, Montana (1962)

Andrew Seng

"The term 'coolie' was a racist term used to describe unskilled, low-wage, physical laborers and indentured servants from Asia."

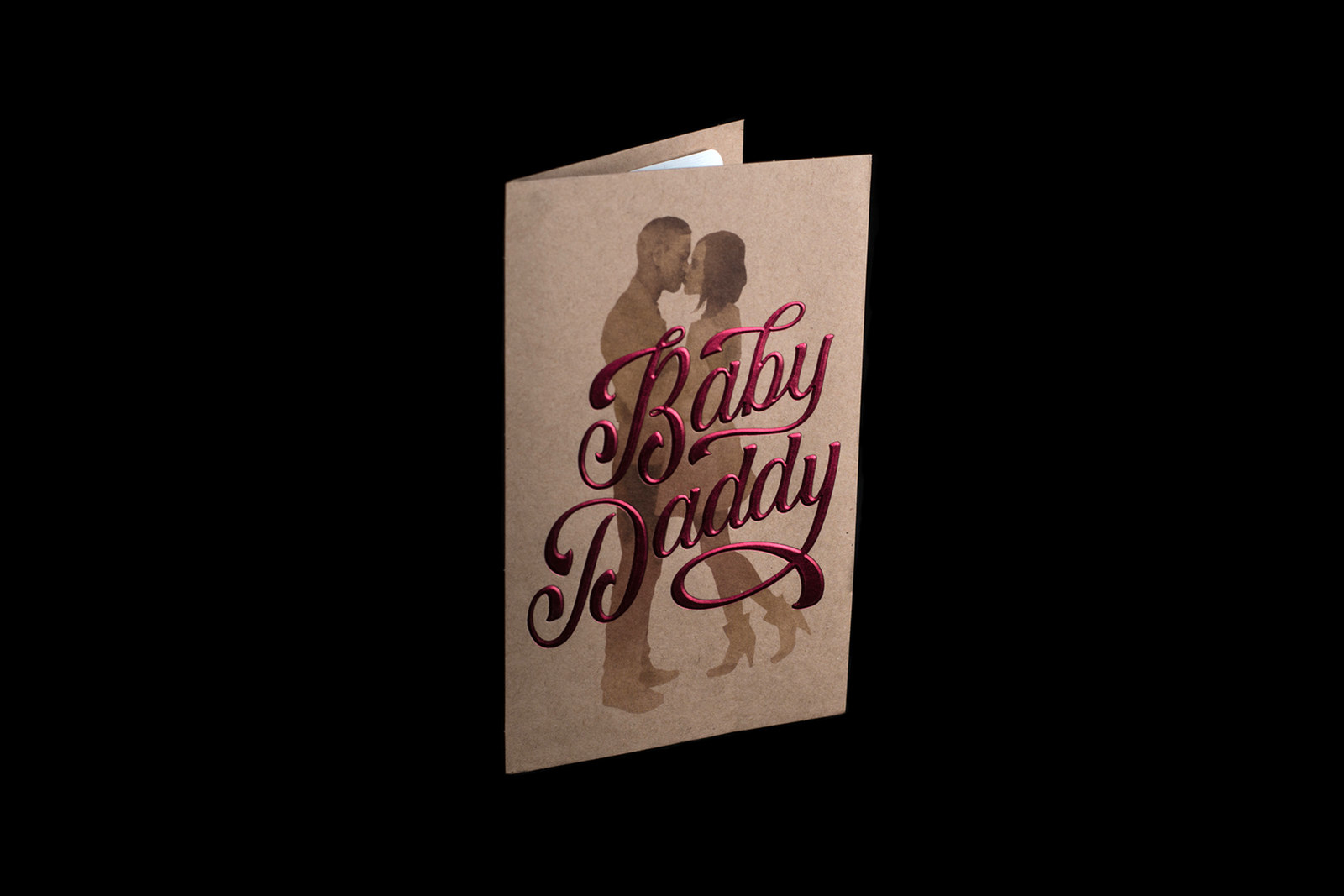

“Baby Daddy” Father’s Day card from Ahoskie, North Carolina (2018)

Andrew Seng

"Customers criticized Target and the American Greetings company for perpetuating racist stereotypes, which led to the item being pulled off shelves in 900 Target stores and 5,300 other big-box stores."

Where do you find these items?

AS: I find items in person at antique stores, or just looking through the shelves at stores and grocery stores. The items found in antique stores obviously tend to be older, and I think it’s important to document and contextualize these older items next to more contemporary items to show the long lifespan and evolution of racism in America.

I think that this project cannot be done without conducting research, writing with context, and holding people accountable. These elements are crucial in understanding how this form of casual racism functions as an arm of white supremacy. Although the project’s visual component is to focus on objects, what is truly being interrogated is the origin and evolution of the harmful ideas that they personify and that still dehumanize black, indigenous, and other people of color today.

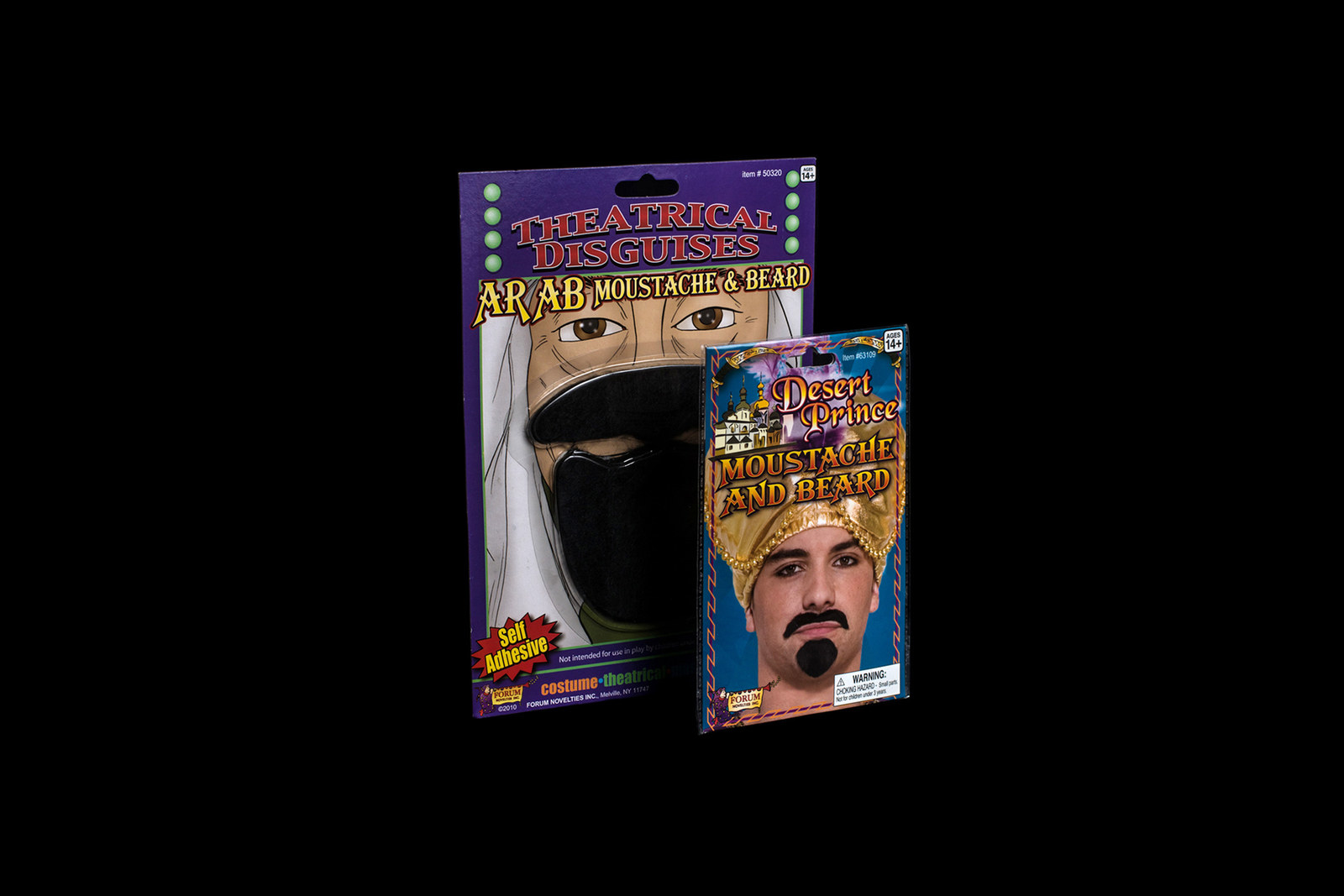

“Arab” and “Desert Prince” mustache and beard from Upper East Side, Manhattan (2010–present)

Andrew Seng

"‘Arab’ and ‘desert prince’ in this context are code for 'Muslim' and draw on racist stereotypes and contribute to physical and radicalized caricatures of how people perceive Muslim men to look alike."

O.J. Simpson Time magazine cover from Valencia, California (1994)

Andrew Seng

"After O.J. Simpson was arrested for the suspected murder of Nicole Brown Simpson and Ron Goldman in 1994, of which he was not found guilty, Time magazine put Simpson’s mugshot taken by the LAPD on the front cover but drastically darkened the image to appear more sinister."

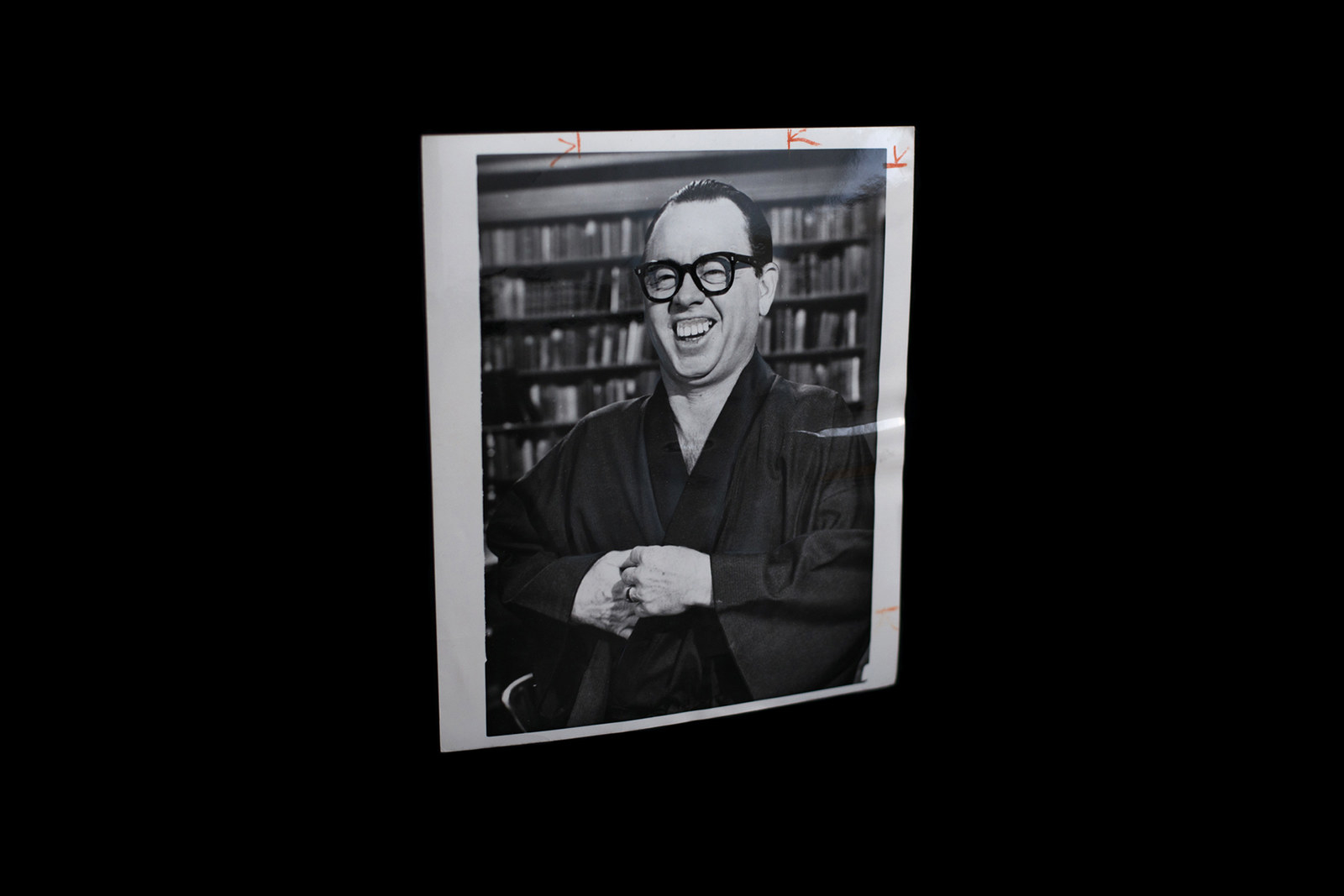

Mickey Rooney in a press photo for Breakfast at Tiffany’s from Memphis (1961)

Andrew Seng

"Mickey Rooney, a white actor, played the character Mr. Yunioshi in yellowface. The studio dressed Rooney as a degrading caricature of a Japanese man in heavy makeup [and] a prosthetic mouthpiece, to give him buckteeth, and taped his eyelids."

Eskimo Pie, worldwide (1921–present)

Andrew Seng

"Because of its roots and usage by nonnatives in a racist, colonial past, the term 'Eskimo' is considered derogatory by some indigenous communities in the Arctic regions today."

“Oriental” Valentine's Day card from Anniston, Alabama (1950s)

Andrew Seng

"The 'perpetual foreigner' is the perception that Asian Americans aren’t considered or viewed as 'real' Americans but as outsiders, regardless of how long their families have established roots in the United States."

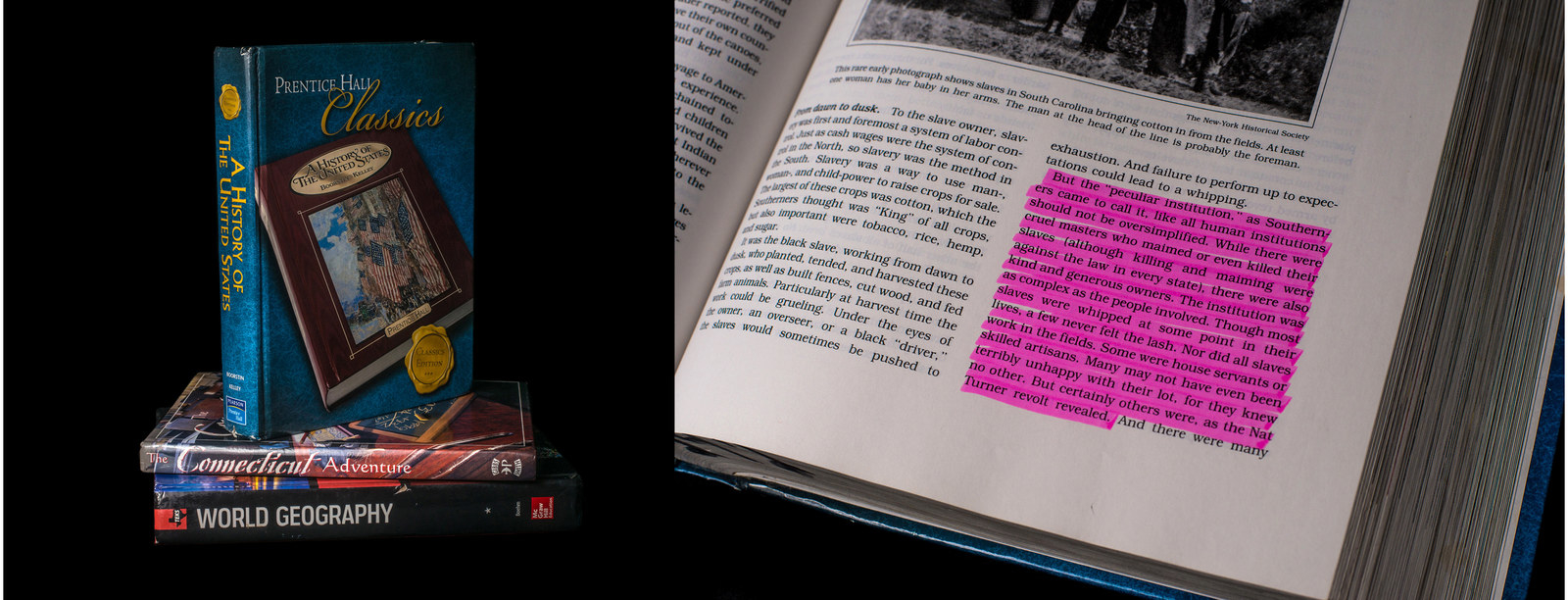

American school textbooks from Texas (2007)

Andrew Seng

"Although slavery is taught in school, textbooks and classroom curricula tend to teach history without context, leaving out crucial details that help students understand its genesis in America, its expansion, and its reliance on shaping whiteness as an identity."

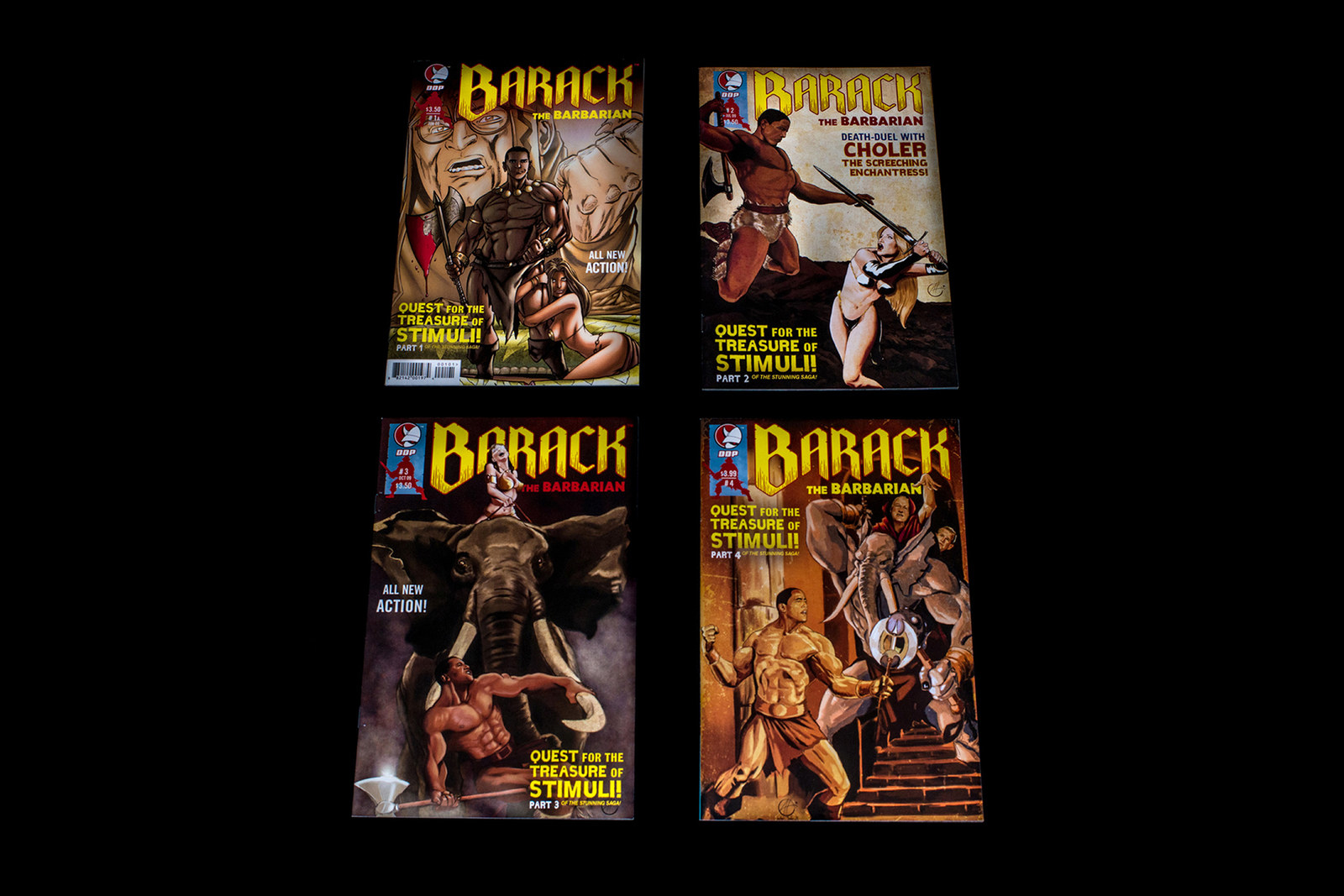

Barack the Barbarian comic books from Chicago (2009)

Andrew Seng

"The comics attempt to shrink a Harvard-educated black man with over 10 years of political experience down to centuries-old racist tropes depicting a hypermasculine savage, an undisciplined sexual being who is both fetishized and feared."

Sambo’s restaurant coaster from Collinsville, Illinois (year unknown)

Andrew Seng

"Once one of the largest food chains in America, Sambo’s had 117 locations across 47 states in 1979 and was known for its reputation for promoting racist iconography, including the name 'Sambo’s' itself."

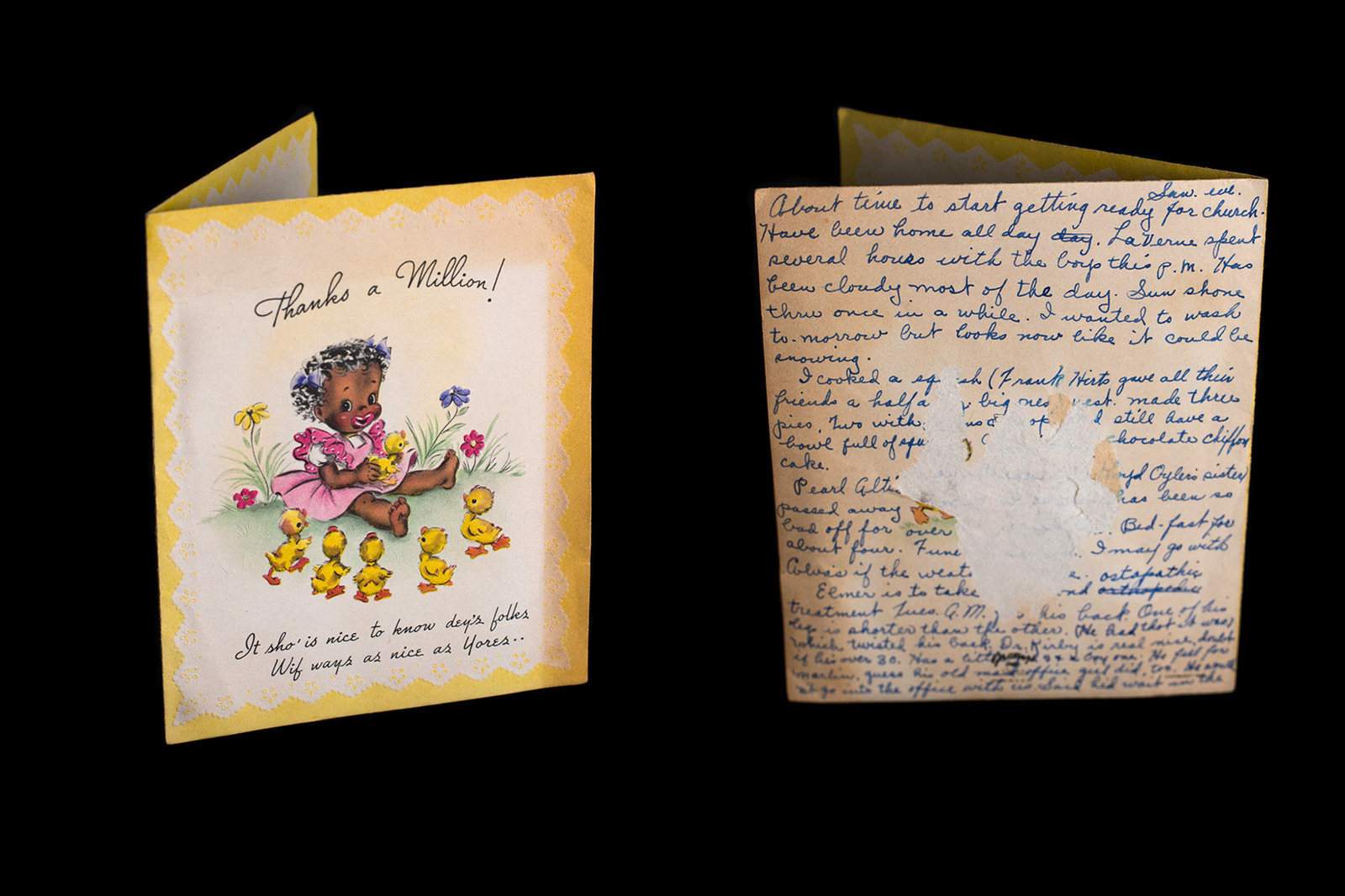

Greeting card from Collinsville, Illinois (year unknown)

Andrew Seng

"Like this greeting card, the 'pickaninny' caricature was often shown with animals, in animal-like positions, crawling on the ground, climbing in trees, all with the intent of dehumanizing black children and conflating them with animals."