“The 1821 Derby at Epsom” by Théodore Géricault

Horses have appeared in works of art throughout history. They have appeared in prehistoric cave paintings, such as those in Lascaux, in temples and tombs of ancient Egyptians and the ancient Greeks, and as monumental statues during classical antiquity. These depictions showed great knowledge of equine anatomy. George Stubbs, an 18th-century English painter, helped further this knowledge by dissecting horse carcasses to learn more about the anatomy of the animal. Stubbs’s detailed anatomical drawings greatly aided later artists.

Horse art peaked during the 19th century when horse racing became a popular form of sport. It was while attempting to paint racing scenes many artists realized that they didn’t know horses enough, especially how they moved when they were galloping.

Horses run so fast that the human eye cannot break down the action of their gait. So a lot of guesswork went into those horse paintings. A running horse was typically shown with the front legs extended forward and the hind legs extended to the rear and all feet off the ground—a posture that is physically impossible. Illustrators and painters probably got this idea by observing dogs, a small, nimble animal that ran with all four legs outstretched, and assumed that a horse’s gait was similar. The result was the characteristic “rocking horse” posture or the “flying gallop”.

The characteristic flying gallop seen in “Baronet” by George Stubbs, 1794.

Another inaccurate depiction of galloping horses. “Ethan Allen and Mate and Dexter” by John Cameron, 1828

Towards the end of the 19th century something happened that significantly changed how artists painted horses.

In 1872, the American industrialist Leland Stanford, founder of Stanford University, hired English-American photographer Eadweard Muybridge to photograph his favorite trotter Occident in action. In those days, photography was a slow process where the film had to exposed for several seconds to make a photograph, so the subject was required to sit motionless during the entire time the photographic plate was exposed. Anything that moved around a lot appeared as a blur.

Muybridge initially believed that it was impossible to capture a good picture of a horse in motion, but after experimenting with various equipment and different chemicals, he managed to produce satisfactory results.

Muybridge had to put his experiments on hold for two years when he went on trial for the murder of his wife’s lover. Muybridge tried to plead insanity, but the jury dismissed it. Surprisingly, the jury also acquitted him on grounds of “justifiable homicide” disregarding the fact that Muybridge had shot his victim at point-blank range in cold blood. It certainly helped that Stanford had arranged for his criminal defense.

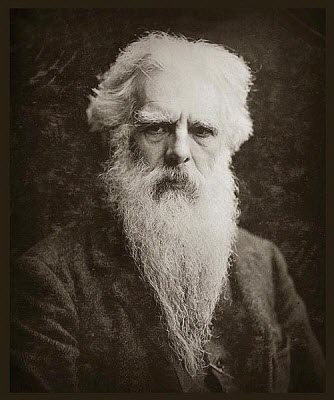

Eadweard Muybridge in 1899.

Muybridge resumed working for Stanford in 1876, continually improving and refining his photographic process. In Shortly after, he managed to capture a single photograph of Occident at a racing-speed gait, serendipitously with all four legs of the animal in air. Stanford was intrigued and he coaxed Muybridge to use multiple cameras so that they could have a sequence of photographs showing the horse’s full gait. This time Muybridge was asked to photograph another of Stanford’s horses named Sallie Gardner.

To freeze the action of a galloping horse was no trivial matter. Muybridge was required to capture multiple pictures within a short time, each exposed no longer than a few thousandths of a second. To achieve the impossible, Muybridge used 12 state-of-the-art cameras he designed himself and lined them up like cannons in a galleon parallel to the horse’s path. The shutters of each camera was controlled by trip wires that lay across the horse’s path and triggered by the horse’s legs. As the horse shot through the trip wires, the sound of the camera shutters firing one after the other in quick succession sounded like a rattling machine gun.

The original 12 photographs of Sallie Gardner. Frames 2 and 3 clearly show the horse completely off the ground with its legs gathered underneath.

Muybridge’s brief filmstrip had captured for the first time ephemeral details the eye couldn't pick out at such speeds, such as the position of the legs and the angle of the tail. It also settled a popularly debated question of the day—is there a moment in a horse’s gait when all four hooves are off the ground at once? Muybridge’s groundbreaking work established that indeed they are, but not like contemporary illustrations depicted. When a horse is completely off the ground, its legs are collected beneath the body and not extended out to the front and back.

Muybridge also prepared a short animated clip using the twelve still images he captured using a device known as the zoöpraxiscope, which was an important predecessor to the movie projector. This animated clip, barely 2 seconds long, called Sallie Gardner at a Gallop is considered to be the world’s first motion picture—a proto-movie. It even has a page at IMDB.

Sallie Gardner at a Gallop

Muybridge’s accomplishment was reported widely throughout the world, and many began to hail Muybridge as a photographic wizard. When it began to appear that Muybridge was stealing all the limelight, Stanford tried to discredit him. In the book Horse in Motion: as Shown by Instantaneous Photography, written by Stanford’s friend and horseman J. D. B. Stillman, Muybridge was mentioned merely as a Stanford employee in a technical appendix. Subsequently, the Britain's Royal Society of Arts, which earlier had offered to finance further photographic studies by Muybridge of animal movement, withdrew the funding. Muybridge ended up suing Stanford, accusing him of wrecking his reputation. But the lawsuit was thrown out of court.

An improved setup Muybridge used to photograph galloping horses. This one employed 24 cameras.

A different galloping horse, Annie G., obtained with the above setup.

Muybridge began to look elsewhere for funding, and eventually found support from the University of Pennsylvania. Under the auspices of the university, Muybridge made tens of thousands of images of animals and humans in motion—people walking up or down stairs, hammering on an anvil, carrying buckets of water, playing sports, and other everyday activities. The images were published in a massive portfolio, with 780 plates comprising 20,000 photographs, in a groundbreaking collection titled Animal Locomotion: an Electro-Photographic Investigation of Connective Phases of Animal Movements. Muybridge's work contributed substantially to developments in the science of biomechanics and the mechanics of athletics. Some of his books are still published today, and are used as references by artists, animators, and students of animal and human movement.

Post a Comment