Muslim voters in the GOP are wondering how, or whether, to cast ballots at a time of anti-Muslim rhetoric from politicians in their own party.

Anwar Khalifa is about as Texan as you can get. He speaks in a sharp twang and cruises around in a Chevy truck with real longhorns mounted on the front. He never skips “worship day,” he taught his three daughters to shoot, and, most important for his standing in Tyler society, the 57-year-old is a lifelong Republican.

For decades, Khalifa’s conservative politics coexisted just fine with his Muslim, immigrant background; his family moved from Egypt to Texas in the late 1960s. He chairs the nominating committee of the local Republican club, and he’s invited a slew of Republican politicians to the mosque his parents helped build. The biggest display in his office is a framed photo of him in a cowboy hat next to then-president George W. Bush at a White House event one Ramadan.

Khalifa’s loyalty to the GOP runs deep, and yet he’s down to maybe two Republican candidates he says he can vote for in good conscience in the November midterm elections. His East Texas ballot will include a candidate who apologized after approving a white nationalist rally, a bankruptcy-plagued radio host nicknamed “the Trump of Texas,” and a state official who compared Syrian refugees to rattlesnakes. Oh, and Sen. Ted Cruz. (“Just evil,” Khalifa said.)

A framed photograph of Anwar Khalifa with former President George W. Bush shares space with Kiwi, Khalifa's pet macaw, in his office.

Khalifa can’t bring himself to vote Democrat, but he sure isn’t voting for that GOP lineup, either.

“I can’t vote for people who are not just anti-Muslim, but who are anti anything that isn’t like them,” he said. “Unless you’re a white person in this country, you don’t matter to them.”

Khalifa is among the last of the Muslim Republicans, a subset of voters that’s disappearing as the GOP moves right on race and religion, with leaders openly demonizing Islam and staying silent when President Donald Trump makes bigoted remarks. Last month, just a couple hours from where Khalifa lives, an internal battle erupted in the Tarrant County Republican Party over calls to remove the party’s vice chair, Shahid Shafi, because he’s Muslim. That fight is still going on.

Muslims aren’t kingmakers, but they have the numbers to influence tight elections in places with high concentrations of Muslims.

Making up just 1% of registered voters nationwide, Muslims aren’t kingmakers, but they have the numbers to influence tight elections in places with high concentrations of Muslims. The Council on American-Islamic Relations, or CAIR, the nation’s largest Muslim advocacy group, flagged five statewide midterm elections where the relatively high number of registered Muslim voters — Democrats and Republicans alike — might swing a tight race: Senate seats in Texas, Missouri, Florida, and Arizona, as well as the dead-heat match for Wisconsin governor.

As with other marginalized communities, Muslims saw a surge of political engagement after Trump’s election, with the emergence of first-time candidates, new lobbying groups, and Muslim-led voter drives. In California, a Muslim Republican, former Pentagon prosecutor Omar Qudrat, will be on the November ballot in a deep blue congressional district. Overall, however, the newfound energy has focused on Democrats. Muslims left the GOP en masse in the post-9/11 era of the Iraq War and the Patriot Act.

Now, under Trump, Muslims who stayed Republican are once again navigating what it means to be in a party where they no longer feel welcome. As the episodes become uglier and more frequent, they face a choice: Leave the party in protest or stay and fight?

Khalifa said the stakes are too high for him to walk away from access that took 25 years to cultivate. His cachet in Republican circles means that when he sees old friends taking potshots at Islam, he can confront them, as he did recently when he asked a buddy running for sheriff to scrap a campaign line about keeping “Sharia law” out of Smith County.

Khalifa with his cockatiel Snow at his home in Tyler, Texas.

“If we get involved, if these politicians know us, when we show up, we matter,” Khalifa said. “When we don’t show up, we don’t exist, and they can do whatever the heck they want to us.”

Six other Muslim Republicans interviewed this month said they too had decided to stay with the party they’ve supported for decades, though some are backing off from active participation or, like Khalifa, abstaining from midterm voting. They argue that even a muted Muslim voice in the ruling party is better than no representation as policies are drawn up to ban, deport, or bomb Muslims.

"This is my party, and I’m going to stay and fight.”

Despite the Trump era’s lack of official channels between the White House and Islamic groups, a handful of Muslim Republicans say they’re still using personal connections to lobby on issues such as the Rohingya crisis in Myanmar, or attempts to block mosque-building projects in the United States. Those slivers of access aren’t nearly enough, they say, making them all the more determined to push back against their party’s narrowing definition of who counts as American.

Suhail Khan, 48, a former Bush administration official and one of the most visible Muslims in the GOP, said he’s excited about recent Republican-led tax and regulatory measures, as well as Trump’s Supreme Court nominees. But the anti-Muslim stances sting coming from a party he joined because of its ideas about individual liberty and limited government.

“It has been a moment of concern, of oftentimes great frustration and anger, absolutely,” said Khan. “But I’ve never questioned whether this is my party or whether I’m a conservative. This is my party, and I’m going to stay and fight.”

Mohamed Elibiary outside his home in Plano, Texas, in 2015.

Muslim Republicans like to invoke the famous line Ronald Reagan used about Democrats to explain their own conflicted affiliation these days: They didn’t leave the Republican Party; the party left them.

“Are we down to two now?” said 43-year-old Mohamed Elibiary, jokingly, when he was asked about the issue.

As a Dallas-based security analyst, Elibiary has helped counterterrorism officials craft policy and handle sensitive cases involving Muslims. In 2011, the FBI, led at the time by Robert Mueller, gave Elibiary the agency’s highest award for public service. Even so, right-wing Republicans called Elibiary a terrorist sympathizer and a secret member of the Muslim Brotherhood. He also was asked to step down from local GOP posts because he accepted an appointment to a Homeland Security committee during the Obama administration.

Elibiary said he hasn’t broken with the party but is sort of on pause, waiting for the right-wing storm to pass. He’s been a Republican for 25 years, he said, so the investment is worth it for him, but he no longer thinks it’s the right choice for Muslims just starting out in politics

Elibiary said he hasn’t broken with the party but is sort of on pause, waiting for the right-wing storm to pass. He’s been a Republican for 25 years, he said, so the investment is worth it for him, but he no longer thinks it’s the right choice for Muslims just starting out in politics.

“I don’t ever try to push young Muslim Americans into the party, because they don’t deserve that kind of bigotry or intolerance,” Elibiary said. “I can put up with it as a 43-year-old. They can’t as a 23-year-old.”

About 8% of American Muslims said they voted for Trump in 2016, according to a Pew Research Center survey. In contrast, polls showed around 40% of Muslims voted for Republican George W. Bush in the 2000 presidential election. When Elibiary first became politically active, most American Muslims from immigrant backgrounds voted along Republican lines, until post-9/11 policies pushed them to identify as independent or Democrat.

Saba Ahmed, the head of the Republican Muslim Coalition and a commentator known for appearing on Fox News in a star-spangled headscarf, said it was a tactical error for Muslims to flee the party in the Bush era.

Saba Ahmed appears on Fox News with a star-spangled headscarf.

“We left a huge void for a voice that was anti-Islamic to talk about us,” she said. “I think the only reason that sort of rhetoric is finding any space is that there’s a huge lack of Muslim voices in the Republican Party.”

Ahmed, a patent attorney who lives in Oregon, said she was such a novelty at the 2016 Republican National Convention in Cleveland that she got face time with leaders she might never have met otherwise. When Ahmed was introduced to former House speaker Newt Gingrich and Rep. Peter King of New York, she said, she spent several minutes confronting them about their anti-Muslim remarks.

The main critique of her approach is that it starts by arguing for Muslims’ humanity, as if the onus is on Muslims to prove not all 1.7 billion of them are terrorists. Many young Muslims are done with condemning attacks they had nothing to do with, or ingratiating themselves to politicians who lash out at Islam. Ahmed defends her methods by arguing pragmatism rather than ideology: Isn’t face-to-face dialogue more effective than shouting from the sidelines?

“I shouldn’t be the first Muslim people talk to,” Ahmed said. “But talking directly makes a huge difference in presenting a different image of Islam, and of Muslims.”

Robert McCaw, CAIR’s director of government affairs, said it’s important to have Muslims active in the GOP because there are so few other channels for influence now that Muslim advocacy groups are frozen out of the White House and the Republican National Committee. He said CAIR and other national Muslim organizations have tried to open talks with the party, “only to be rebuffed.”

McCaw also has tried to get the RNC to delete a question from the “Listening to America” survey on its website: “Are you concerned by the potential spread of Sharia Law?” The same question popped up later in a Trump campaign email. The fact that the question is still up on the GOP website, McCaw said, shows that “from the very top of the Republican Party, they are fearmongering about Sharia.”

Republican National Committee officials did not respond to messages seeking comment.

“Muslim Republicans should engage the GOP and challenge it to be that big-tent party McCain advocated for in his final message to Americans,” McCaw said, referring to Republican Sen. John McCain of Arizona, who died Aug. 25. “Right now, the soul of the Republican Party truly is divided on whether they support white supremacy and tribalism, or they’re an inclusive party looking toward the future.”

Khalifa chats with friends before Friday prayer at the East Texas Islamic Society in Tyler.

Tyler’s main mosque, the East Texas Islamic Society, sits across from the Oil Palace, a venue where country and cumbia stars perform on tour stops.

Khalifa’s parents helped to build the mosque when there were so few Muslims here that they only filled a single row at Friday prayers. Now, dozens of Muslims from all backgrounds come to the Friday service and others attend a new, second mosque.

One recent Friday, Khalifa was greeted warmly with bear hugs and salaams, though in truth his relations with some members are strained because of internal leadership conflicts as well as Khalifa’s politics. Not long ago, a Palestinian member of the congregation lashed out at Khalifa publicly because of his support for the state House campaign of a rabbi friend, Neal Katz, who supported the Trump administration’s move of the US Embassy in Israel from Tel Aviv to contested Jerusalem.

After that incident and other flare-ups, Khalifa went weeks without coming to the mosque, a painful absence for him. He said Muslim leaders call him up to serve as an interlocutor with the East Texas political class, but are reluctant to support him publicly because of his politics.

“I kind of had to back off. It’s a shame,” Khalifa said. “Either you want me doing stuff in the community and you support me, you back me, or I don’t do anything in the community because I don’t have your backing. It can’t be both ways.”

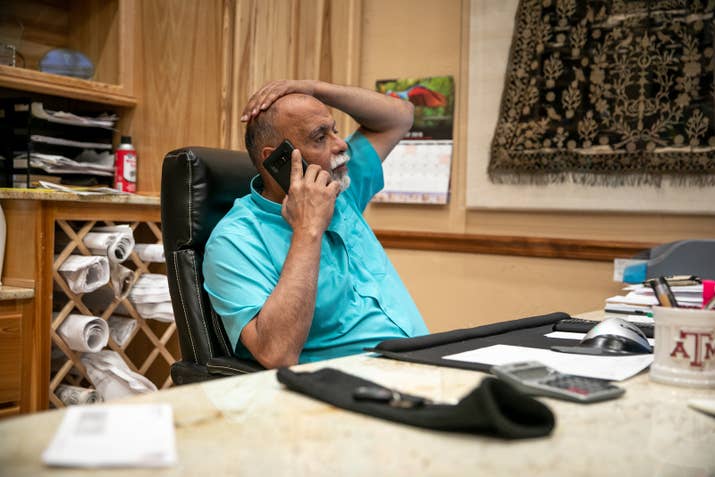

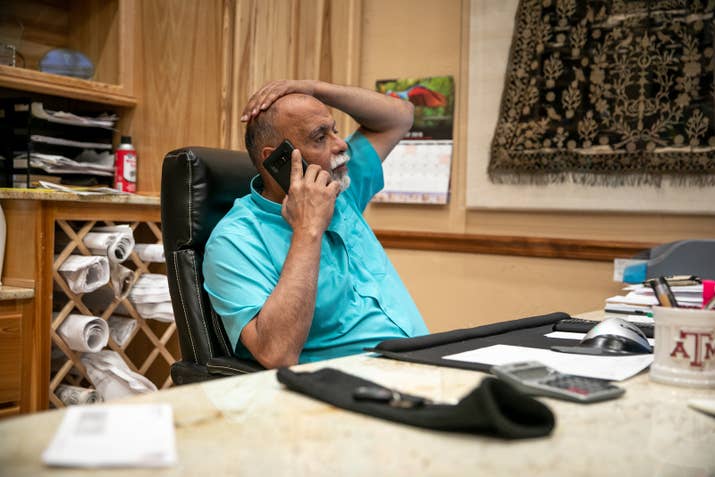

Khalifa in his home office.

Khalifa feels the squeeze from the Republican side, too. There was a time, Khalifa said, when he could get just about any politician to come to the mosque. Khalifa said even Rep. Louie Gohmert, a tea party stalwart, paid a visit before he transformed into one of the most strident anti-Muslim voices in Congress. Now, he said, Gohmert won’t take his calls. (Gohmert’s communications director didn’t respond to an email seeking comment.)

That feeling of losing ground, in both Muslim and Republican spaces, is difficult for Khalifa, who takes pride in how his Egyptian parents carved out a corner of Texas where Muslims opened businesses and lived as examples of their faith’s tenets of charity and community service.

Fatima Elkabti, 30 and Mohammad Arif, 29, a Democratic Muslim couple Khalifa befriended when they moved to Texas four years ago, said they’ve watched Khalifa’s disappointment grow as Trumpism spreads through the party and state he loves.

Sometimes, they said, it seems like Khalifa refuses to accept that the Texas that welcomed his Egyptian parents is now a place where Arif’s dental office was defaced with white nationalist stickers within a week of opening last year. At Elkabti’s optometry office, a photo of her in a hijab is displayed prominently outside the door in part to weed out bigots who might cause trouble if they show up for an appointment to find that their eye doctor is Muslim.

Elkabti and Arif have a toddler son, and Elkabti is pregnant again. They’re leaving Texas soon for Louisville, Kentucky, the birthplace of boxing legend Muhammad Ali, and Arif jokes that at least people there won’t freak out at a Muslim name. They love a lot about Tyler, Elkabti said, but it’s draining to feel like your whole life has to be a PSA for Islam. One of the things she admires about Khalifa is that he treats that burden as an opportunity.

Mohammad Arif and Fatima Elkabti dine out with their son, Zakaria, in Tyler.

“He’s a pillar of this community, and I don’t just mean the Muslim community, but for Tyler,” she said. “He perfectly straddles these two worlds.”

Khalifa was born in Egypt, but reared in Texas. He went to high school in Dallas and college in South Carolina and Texas. In the mid-1980s, he went back to Cairo for an internship at a bank, where he met his wife, Hala. He brought her to Tyler, where they had three daughters and launched a construction company, Pyramid Homes, after he was laid off from a Texas chemical company.

“In East Texas, you’re Republican or you don’t matter.”

Hala said she and their daughters do not identify as Republican and don’t fully get what Khalifa loves about the party. He said he was drawn to ideas about small government and entrepreneurship in the Nixon years, and learned along the way that GOP affiliation was vital for breaking into Tyler’s business and political classes.

“In East Texas, you’re Republican or you don’t matter,” he said.

Khalifa became a community fixture. He was a Muslim voice on a local religious council, he was a police chaplain, and the governor’s office invited him to serve on the Texas Human Rights Commission. He’s volunteered with Habitat for Humanity and an AIDS prevention group. He’s currently planning an appreciation dinner for local law enforcement, though some of the other organizers are balking at his request that it be alcohol-free.

A photo of Khalifa with the former vice president, Dick Cheney, in Khalifa's office.

After years of showing up for virtually every cause in town, Khalifa finds it galling that some fellow Republicans would now look at him with suspicion solely because of his religion and immigrant background. The fact that they overwhelmingly voted for Trump wasn’t a surprise, he said, but it was still heartbreaking to see party loyalty valued more than standing against racism and bigotry.

“The fact that party has become more important than country is disturbing. Party first. Party, party, party,” Khalifa said. “On Charlottesville, Trump said there were good people on both sides. These were white supremacists, people who hate, who were there for a specific reason.”

The outbreak of hatred might be shocking to some Americans, but Khalifa said his years in the trenches among East Texas conservatives has prepared him for this moment. About six years ago, he said, Brigitte Gabriel, one of the most extremist anti-Muslim figures in the country, came to Tyler on the right-wing lecture circuit. Khalifa took a group of Muslims and sat in the front row, he said, “just to say, ‘We’re here, and we’re not going anywhere.’” Khalifa said they’d agreed beforehand not to interrupt. He took notes of all the Republican friends and acquaintances he saw at the talk, and started making calls afterward. He’s not sure he swayed anyone, but at least Gabriel didn’t get the last word.

“I called them up and asked, ‘Why the hell did you go to that?’” Khalifa said. “And then I told them, ‘Y’all need to come to our open house at the mosque.’”

Post a Comment